An old wedding photograph might be the only image of our ancestors that survives. A couple of reasons for this are, firstly, the special occasion justified the expense of hiring a photographer, and secondly, descendants often preserved an early studio wedding photo preferentially over a later snapshot of daily life. Not only are these wedding photos treasures in their own right, but they can furnish clues that help us date other old images. They also reflect societal norms and expected gender roles. This was highlighted for me when I recently visited Lougheed House in Calgary.

The new temporary display at Lougheed House runs June 8 to October 16 and is called “Something Old, Something New: 125 years of Wedding Fashion.” The time frame encompassed by the exhibit was chosen to celebrate the 125th anniversary of this historic structure. Twelve dresses and numerous accessories, with examples from different cultures, cover those years. I found the scope a bit too large and would have preferred to view a more focussed display, with a narrower time range; however, I can appreciate their goal. What better way to celebrate an anniversary than remembering the finery of weddings through the years? All of the items were beautiful, but with such a large period, I would have loved to see more dresses to flesh out the time span.

An interesting aspect of this exhibit was the attempt to relate fashion to social history. The change from the use of corsets and bustles in the 1880s to today’s more flowing and revealing styles demonstrates the changing roles of women through time. Nowadays there is a greater individuality in wedding clothing and a personalization of wedding ceremonies, which often meld different cultural traditions. This is reflected in today’s broader definition of marriage which is simultaneously more inclusive and more basic than it was in the past: the uniting of two people who love each other and are committing to spending their life with each other, regardless of their individual ethnicity, religion or gender identity.

Being interested in history, I am keen to understand how fashion reveals its era. I recall a textbook example from eons ago when I was an archaeology student. In explaining how changes in the frequency of an artifact’s style can signal when it was manufactured, the writer discussed blue jeans. Bell bottoms had just transitioned from the epitome of contemporary into the discarded realm of passé. Any artifact has a lifespan, with a tentative introduction, swelling to a peak of popularity and then dwindling off into oblivion. The rapid rate of change in clothing styles provides a good indicator of time, so long as one can recognize when a reinterpreted feature from the past has been incorporated in a new design (think about today’s flared jeans).

As well, practical concerns like budget and functionality also determine attire; not all of us can afford haute couture nor would most of us find such avant-garde clothes useful. Thus, as always, looking at the whole context can give a more accurate understanding than focussing on only one aspect.

My work on the Glenbow Town and Quarry Project for the Archaeological Society of Alberta (Calgary Centre) has allowed me access to some historic wedding photographs. They provide examples of clues that can be used to decipher dates and indicate some aspects of social history. The earliest in my collection is that of Hugh and Annie McLean from 1898. The leg-o-mutton sleeves on Annie’s dress, with the puff at the shoulder, fitted arm, and ruffle at the cuff are signposts for the 1890s. These combined with the hourglass silhouette, high collar, and the bride’s curly but contained hairstyle, reflect the date. Obviously, such a form-fitting dress would have restricted movements that we take for granted today.

Hugh and Annie McLean 1898

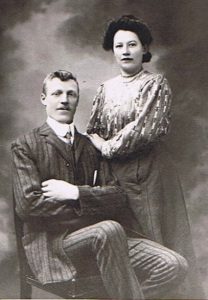

Two wedding photos from 1910 illustrate some of the variability in style at that time. The first is of Ernie and Alice Silvester. They are arranged in a similar pose as Hugh and Annie were. The advantage of seating the groom is that the faces of the couple are closer together, compensating for the difference in their stature. Additionally, by standing, the bride could show off the details of her dress. This couple married in England and immediately set sail to homestead in Canada. Alice wore a two-piece ensemble for her wedding day, better suited to reuse than an extravagant gown would have been. Her clothes are not as fitted as the dress in the earlier photo, though her collar is still high and her sleeves are full-length. By this time, corsets had evolved from wasp-waisted hourglasses to a more S-shape where the bodice puffed forward. Her hairstyle signals the era, as does Ernie’s high, round-edged collar.

Ernie and Alice Silvester 1910

The second wedding portrait from 1910 shows Cecil and Jessie Edwards, who married in Edmonton, Alberta. Cecil sports a stiff collar in the same style as Ernie’s. Even with only a portion of Jessie’s bodice visible, there are dating clues. Again, there is the high collar with the little lace ruffle and a more rounded shoulder line than Annie’s dress. This bodice has detailed edging and trim to reflect the important occasion. It appears that the dark portion of her outfit was a separate piece that could be removed, another example of practical considerations, even for special outfits. The key to the date, however, is her hairstyle. Similar to Alice, Jessie’s hair is rolled up away from her face, but the centre part and flat crown relate to the preference for extremely large-brimmed hats at this time.

Cecil and Jessie Edwards 1910

Less restrictive fashions for women in the early 1900s developed from the necessity for freer movement. By this time, women were taking part in sports like tennis and bicycle-riding, so garments had to allow a greater range of motion. Additionally, the active role of women in caring for the home without the aid of servants, and women’s participation in more physical labour in a pioneer setting, demanded less fussy and restrictive clothing. This trend of increasingly practical clothing for women continued right through to the Second World War, when women took on more of the roles vacated by men who had left to fight.

Wedding photographs offer the family historian a unique opportunity. Because they are easily dated by reference to other historic documents, like marriage registrations, they can provide clues to the age of other images; an analysis of the fashions depicted can reveal diagnostic traits to measure other images against. As well, understanding the fashions worn by our ancestors can hint at the social world they lived in, with its complex expectations and restrictions. Even today, our clothing signals how we choose to fit into what society prescribes.

This article was originally printed in the BERGEN NEWS and is being reprinted with permission.